- Nest in mature coniferous forests.

- Perch at forest edges where they catch insects on the fly.

General Terms and Conditions / All Rights Reserved

All the features necessary to navigate this report can be found in the bookmark on the left side of the screen. These features include:

The main menu is accessed through the hamburger menu. This report is divided into seven sections, including the Report Summary. From the menu, you can access any of the chapters and their subsections from anywhere in the report.

The "page turner" arrows at the bottom left of your screen will sequentially take you through the report, page by page. For example, press the right arrow to move from Section 2.1 to Section 2.2.

Tip: If you’re interested in the full report, we encourage you to start with the Introduction in Chapter 1 and use the page turner function to sequentially navigate through the report.

Summary of how implementing variable retention in harvest areas can increase bird diversity.

.svg)

Retention patches within regenerating harvest areas introduce structural and compositional heterogeneity that is beneficial for wildlife. This study explored how variable retention in regenerating harvests may speed up forest bird use of harvested areas. Results show that any amount of retention is valuable for some songbirds, but benefits take a minimum of 10 years to come into effect.

Introduction

Forest songbirds, like the Yellow-rumped Warbler, have different habitat requirements for nesting and foraging.

Features like canopy cover, snag density, and forest patch size influence how suitable retention patches are as habitat for different forest birds.

The presence and diversity of bird species help indicate how effectively forest retention patches provide habitat within managed landscapes.

More About Retention

As a result, the rules are flexibly applied, leading to a variety of patch shapes and sizes. Understanding how birds respond to these retained patches helps evaluate whether current retention practices effectively support wildlife habitat in managed forests.

Methods

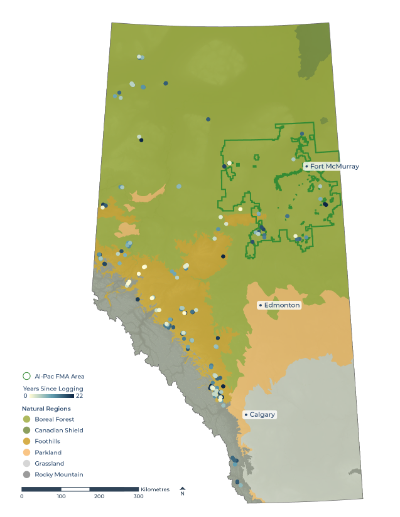

Map of Study Sites. Map of study sites in forested regions of Alberta where birds were sampled in regenerating harvest areas with retention patches.

More About the species

These six species have different forest habitat preferences, nesting and foraging behaviours, and vary in their tolerances to forest harvesting. These species are not strictly interior forest or old forest specialists, and have been documented using regenerating harvests with varying amounts of tree retention. They include:

Key Results

This research found that species respond differently to retention patches, and that these responses shift over time. Overall, birds are observed at areas with retained live trees more quickly than those without. However, patch shape and size influenced how the retained areas were used.

Tennessee Warbler was 2-3 times more abundant.

Olive-sided Flycatcher abundance decreased over time.

Patches closer to intact forest were used more often.

White-throated Sparrow prefer smaller retention patches.

Yellow-rumped Warbler prefer patches with more edge.

Retention patches did not provide suitable habitat for Ruby-crowned Kinglet.

Red-eyed Vireo prefer larger patches with less edge.

Management Implications

Until longer-term outcomes are known, a balanced approach of mixing small patches for connectivity with larger remnant forests offers the best strategy for maintaining bird diversity in managed landscapes.

References

Lebeuf-Taylor, I., E. Knight, E. Bayne. 2025. Improving Bird Abundance Estimates in Harvested Forests with Retention by Limiting Detection Radius through Sound Truncation. Ornithological Applications 127: 1–13. Availabe at: https://academic.oup.com/condor/article/doi/10.1093/ornithapp/duae055/7824177.

Fedrowitz, K. et al. 2014. Can Forestry Help Conserve Biodiversity? A Meta‐analysis. Journal of Applied Ecology 51: 1669–79. Available at: https://besjournals.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/1365-2664.12289.

Government of Alberta. 2024. Alberta Timber Harvest Planning and Operating Ground Rules. Available at: https://open.alberta.ca/publications/timber-harvest-planning-and-ogr-2024.

Franzreb, K.E. 1978. Tree Species Used by Birds in Logged and Unlogged Mixed-Coniferous Forests. Wilson Bulletin 90(2): 221–38. Available at: https://digitalcommons.usf.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=8101&context=wilson_bulletin.

Contributor

Her research interests lie in improving methods of linking bird populations to changing landscapes for more effective conservation.

This research was supported by Alberta-Pacific Forest Industries Inc. through a Mitacs Accelerate grant (Number IT34177), the Forest Research Improvement Alliance of Alberta (FRIAA), the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC), the Northern Scientific Training Program (NSTP), and the University of Alberta Northern Research Awards (UANRA).