The study examined how habitat loss and fragmentation affect two old-forest songbirds in Alberta’s boreal forest—the Canada Warbler and Black-throated Green Warbler. Both species were negatively impacted with increasing habitat loss and fragmentation, underscoring the importance of maintaining large, connected tracts of mature forest to sustain old-forest specialists.

More about the species

Status: SARA-Threatened[2] | COSEWIC-Special Concern[3]

- During the breeding season, associated with mature mixed and deciduous forest habitats, increasing in abundance with stand age[5].

- Nests on or near the ground in dense vegetation and forages in the shrub layer or lower canopy, often near streams or wetlands.

- Declined by 71% since the 1970s[4], largely due to habitat loss and fragmentation on their breeding and wintering grounds.

Status: ESCC-Special Concern (recommendation)[6]

- Old forest interior specialist that requires mixedwood stands over 80 years old for breeding, increasing in abundance with stand age[7].

- They strongly prefer foraging on White Spruce trees, where they search for insects in the outer part of the branches, allowing them to coexist with other warblers that use different parts of the tree crown.

- Builds nests on branches close to the trunk, well-concealed by foliage.

Research Approach

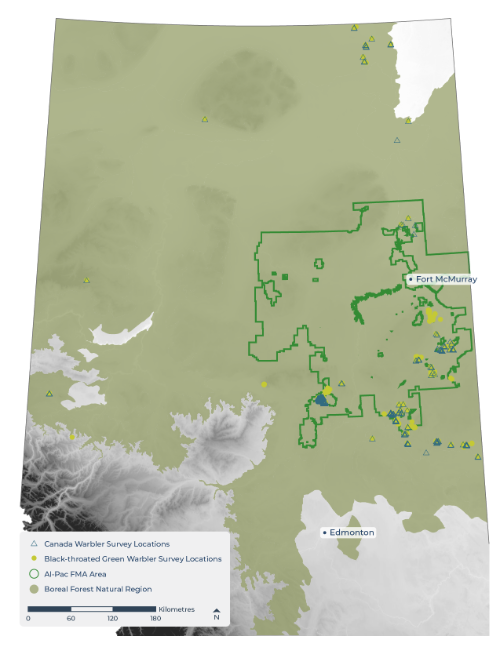

- Canada Warblers were surveyed at 395 locations and Black-throated Green Warblers at 508 locations in mature deciduous and mixedwood forests 80-140 years old in Alberta’s boreal forest.

- At each site, only suitable mature forest habitat for each species was included when calculating habitat amount, ensuring measures of habitat reflect what matters to each warbler.

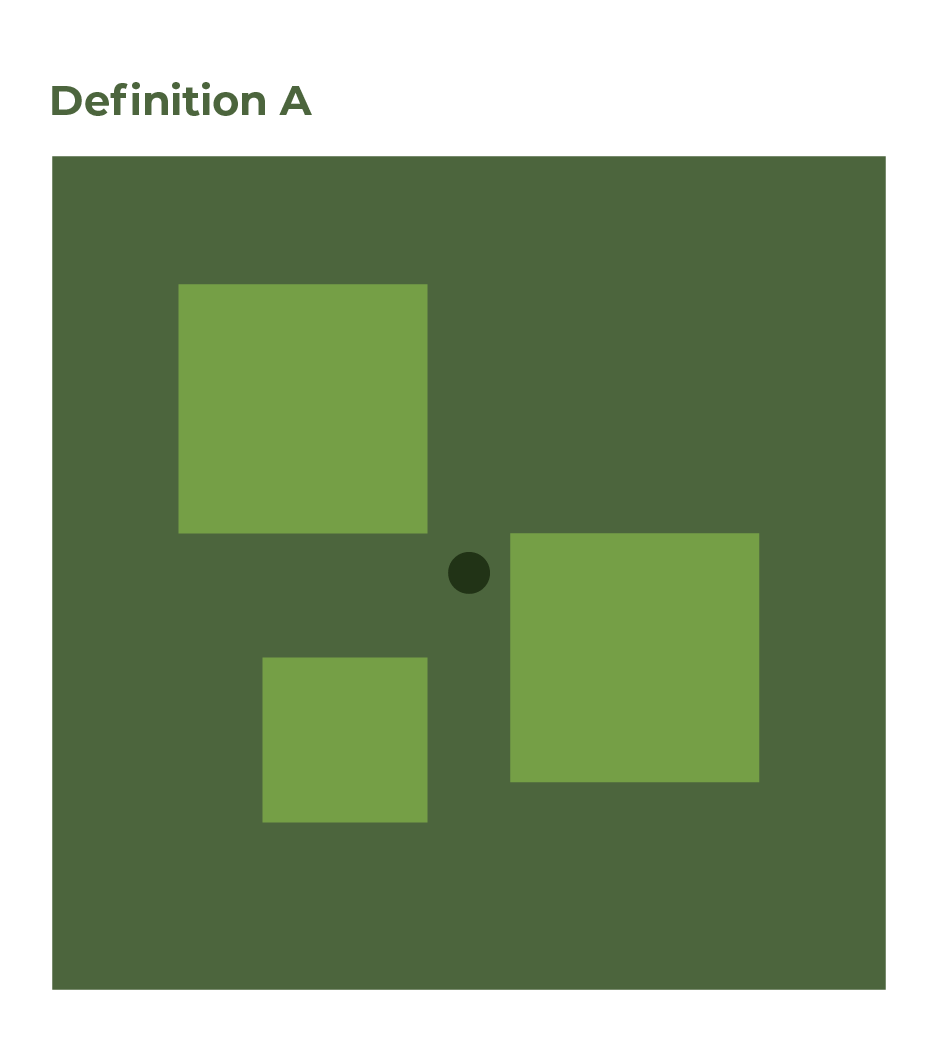

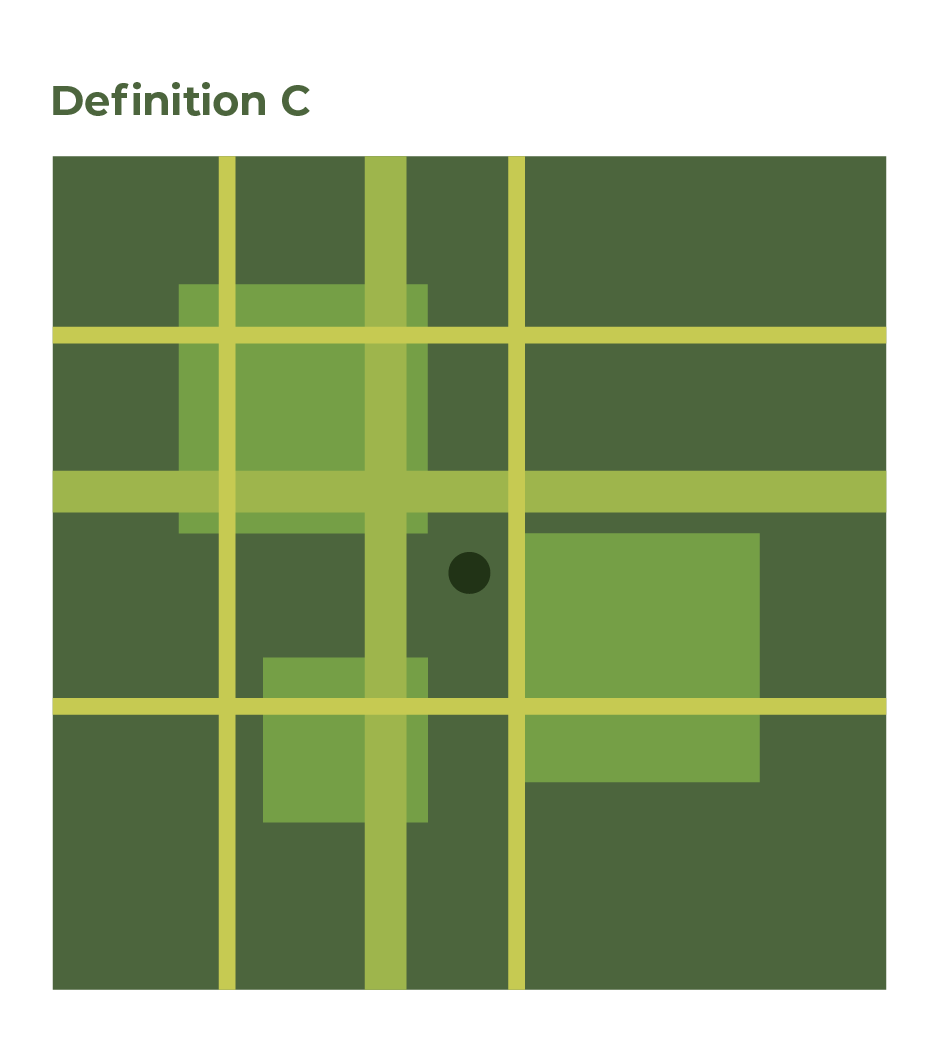

Within this suitable habitat, the studies quantified fragmentation using three increasingly refined definitions of fragmentation (also see figures below):

- Definition A: includes large polygonal disturbances (forest harvest blocks, well pads, industrial facilities).

- Definition B: includes large polygonal disturbances from Definition A plus wide linear features (roads, pipelines >8 m wide, transmission lines).

- Definition C: includes all human disturbances, even narrow seismic lines (4-8 m wide).

Researchers then examined how these species are affected by habitat loss and fragmentation by measuring their occurrence (presence or absence) at survey sites across these three fragmentation definitions and spatial scales to assess:

- if their reaction to fragmentation changes with habitat amount,

- which disturbances influence their presence, and

- which scales matter most for habitat loss and fragmentation

For Canada Warblers, multi-year survey data allowed researchers to go further—tracking not just where birds were found, but whether new birds moved into sites over time (colonization) or disappeared from previously occupied sites (extinction). This reveals how fragmentation affects population change, not just current distribution.

Map of Survey Locations. Map of Canada Warbler and Black-throated Green Warbler survey locations in mature deciduous and mixedwood forests 80-140 years old in Alberta’s boreal forest.

ARU used to record bird songs

Definition A. Includes large polygonal disturbances (forest harvest blocks, well pads, industrial facilities).

Definition B. Includes large polygonal disturbances from Definition A plus wide linear features (roads, pipelines >8 m wide, transmission lines).

Definition C. Includes all human disturbances, even narrow seismic lines (4-8 m wide).

Key Results

This research examined three key questions about how fragmentation affects two species at risk: Does fragmentation matter more than habitat amount? Which types of disturbance influence their presence? And at what spatial scales are habitat loss and fragmentation most important?

Fragmentation vs Habitat Loss

Both species had reduced occurrence in more fragmented landscapes

Fragmented landscapes are less likely to be colonized by CAWAs

Continuous, connected canopies are key for BTNWs

Fragmentation has effects distinct from habitat loss, as both species showed reduced occurrence in more fragmented landscapes, even when accounting for the amount of available habitat.

Canada Warblers

- Canada Warblers were much less likely to be found in fragmented landscapes, even when plenty of old forest remained. Sites with more edges (more fragmentation) were 46% less likely to be occupied, showing that fragmentation directly limits where they nest.

- Additionally, observing birds over multiple years revealed that fragmentation does not just reduce where birds are found today, it actively prevents new birds from colonizing areas and accelerates how quickly they disappear from occupied sites.

- This means fragmented landscapes continuously lose value over time, with populations declining year after year rather than reaching a stable lower level.

Black-throated Green Warblers

- Black-throated Green Warblers were also less likely to occur in areas where both habitat loss and habitat fragmentation were high; however, areas with more old forest on its own did not explain their presence well

- What mattered most was whether the forest was continuous and connected. This may reflect their behaviour as canopy specialists that rely on large, contiguous stands.

Together, these findings show that fragmentation has lasting impacts on old-forest specialists. It not only lowers the number of sites used for nesting today but also reduces the ability of populations to recover or expand in the future.

Influence of Scale

CAWAs avoid nesting in areas with a lot of edge

CAWAs like to nest near other CAWAs

BTNW needs continuous habitat at the territory and home range scale

Both the Canada Warbler and Black-throated Green Warbler responded strongly to both the amount of habitat and the degree of fragmentation in the landscape, but at different scales:

Canada Warblers

- Fragmentation consistently reduced occurrence, especially at the home range (78 ha) and landscape (314 ha) scales. In other words, even large forested landscapes lose value when heavily dissected, as these birds avoid settling and nesting in areas with lots of edge.

- This shows that it is not just how much forest exists, but whether it remains in large, intact patches. Their tendency to gather near other Canada Warblers may help explain why they avoid fragmented areas.

Black-throated Green Warblers

- The key finding was the interaction between habitat amount and fragmentation, especially at the territory (7 ha) and home-range (78 ha) scales. When fragmentation was high, they were absent no matter how much suitable forest habitat was there.

- But when fragmentation was low, their chances of occurring rose quickly as habitat increased.

- This suggests that they gain from more habitat only when it is continuous, consistent with how they defend territories and forage daily in the canopy of mature forest

Overall, these results demonstrate that preserving habitat alone is insufficient if it is fragmented. For both species, the spatial arrangement of habitat is what determines whether populations can persist, recolonize, or expand through time.

Disturbance Type

Large disturbances can be barriers for CAWAs

Narrow features disrupt BTNW forest canopy habitat

When different types of disturbance were compared in terms of how they break up the forest, the two species showed clear differences in how they respond in multi-use landscapes.

Canada Warblers

- Canada Warblers were most sensitive to large disturbances such as harvest areas and wellpads, which likely act as barriers that break up the forest.

- Narrow seismic lines had weaker effects, likely because birds can cross or use them when vegetation grows back[4]. But when many lines were present, they added to overall fragmentation and reduced suitability.

Black-throated Green Warblers

- Black-throated Green Warblers were sensitive to all disturbance types—large harvest areas, wide corridors such as pipelines and roads, and even narrow seismic lines reduced their occurrence.

- Unlike Canada Warblers, they were less tolerant of narrow features, which may be due to these features breaking up the canopy where they spend their time foraging and singing.

References

Hart, T., E.M. Bayne. 2025. Habitat Amount–Fragmentation Interactions Drive Canada Warbler Dynamics across Spatial Scales. Avian Conservation and Ecology 20(2). Available at: https://doi.org/10.5751/ACE-03001-200215.

Environment Canada. 2016. Recovery Strategy for Canada Warbler (Cardellina Canadensis) in Canada. Species at Risk Act Recovery Strategy Series. Environment Canada, Ottawa. vii + 56 pp. Available at: https://www.sararegistry.gc.ca/virtual_sara/files/plans/rs_canada%20warbler_e_final.pdf.

COSEWIC. 2020. Canada Warbler (Cardellina Canadensis): COSEWIC Assessment and Status Report 2020. Available at: https://www.canada.ca/en/environment-climate-change/services/species-risk-public-registry/cosewic-assessments-status-reports/canada-warbler-2020.html.

Gregoire, J.M., R.W. Hedley, E.M. Bayne. 2022. Canada Warbler Response to Vegetation Structure on Regenerating Seismic Lines. Avian Conservation and Ecology 17(2). Available at: https://ace-eco.org/vol17/iss2/art26/.

Alberta Biodiversity Monitoring Institute and Boreal Avian Modelling Project. 2023. Canada Warbler (Cardellina canadensis). ABMI Website: https://abmi.ca/species/cardellina-canadensis.

Alberta Environment and Sustainable Resource Development. 2014. Black-throated Green Warbler, Bay-breasted Warbler and Cape May Warbler Conservation Management Plan 2014-2019. Alberta Environment and Sustainable Resource Development. Species at Risk Conservation Management Plan No. 10. Edmonton, AB. 33 pp. Available at: https://open.alberta.ca/dataset/d00a2147-4c28-4af0-a6f1-880159b8d859/resource/39c8d4d8-ba18-4fa5-a56b-363f42b3a68b/download/sar-warblermanagement-mar2014a.pdf.

Alberta Biodiversity Monitoring Institute and Boreal Avian Modelling Project. 2023. Black-throated Green Warbler (Setophaga virens). ABMI Website: https://abmi.ca/species/setophaga-virens.

Contributor

Taylor is a PhD student specializing in landscape ecology and population biology, focusing on boreal forest songbirds. Her research uses quantitative methods to examine how industrial activities—such as forestry and energy development—affect wildlife populations and biodiversity. She aims to conduct applied research that informs policy and conservation strategies, particularly for at-risk species in multi-use landscapes.

This research was supported by the Alberta Biodiversity Monitoring Institute, the Alberta Conservation Association (ACA Grants in Biodiversity), Alberta-Pacific Forest Industries Inc., the Forest Resource Improvement Association of Alberta, and the Oil Sands Monitoring Program (OSM). While this work was funded under OSM, it does not necessarily reflect the position of OSM.

.svg)