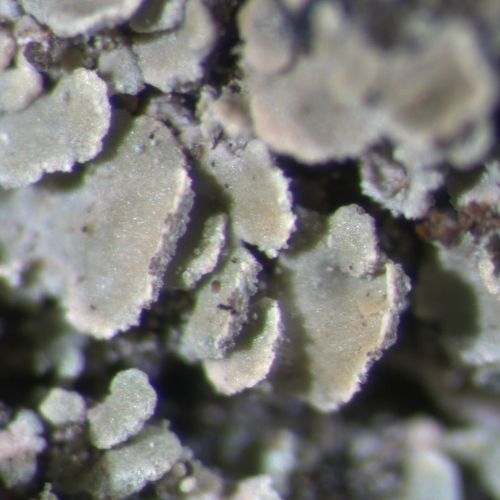

Blue Columbine

- Overall, 42% of species had net declines in habitat suitability driven by both natural changes and human footprint.

- On average, the net effect of natural processes (i.e., wildfire and forest aging) on habitat suitability was greater than the effect of human footprint.

- New forestry footprint reduced habitat suitability for about two-thirds of species (66%), though this impact was partially offset by the recovery and aging of previously harvested areas.

Methods for summarizing attributions of habitat change are described in Section 1.3.3.

Results

We present overall results for each of six taxonomic groups, showing the distribution of predicted species’ responses to each type of land base change in the Al-Pac FMA area between 2010 and 2023.

In general, the results show that:

- In the Al-Pac FMA area, current species results show that, on average, natural changes on the land base—such as wildfire and the aging of naturally disturbed stands—had a greater overall effect than the human footprint. Of the 57,683 km² of undisturbed native habitat present in 2010, only 3.2% was altered by human activities. In comparison, wildfire affected 9.9% of the area, while the remaining 86.9% remained as undisturbed native habitat. As a result, natural processes like wildfire and forest aging were the primary drivers of changes in habitat suitability during this period.

- Land base changes on habitat suitability due to both fire and aging had substantial effects on many species in all taxonomic groups except mammals, ranging from -38% to +37%. For birds, soil mites, vascular plants, lichens, and mosses, there were wide distributions of responses to both fire and aging, with species responding both positively and negatively.

- However, the main drivers of change can vary depending not only on how much area is affected, but also on which habitats are impacted by both wildfire and human activities. For example, some species, such as the White-breasted Nuthatch, experienced larger declines in habitat suitability (-4%) from human footprint than expected based on the amount of new disturbance alone, highlighting the importance of considering both the extent and location of each type of disturbance.

- Overall, habitat suitability declined for 66% of species due to new forestry footprint, with changes ranging from -11% to +16%, though impacts varied by taxonomic group. Most lichens, soil mites, and mosses declined, while many birds and vascular plants that prefer open or early-successional habitats benefited from harvested areas.

- Aging of older forestry areas tended to offset new forestry, with habitat suitability improving for 66% of species, resulting in a smaller net effect of forestry compared to that of new forestry alone for all taxonomic groups.

Birds

The graph below shows the distribution of bird species' responses to each type of land base change in the Al-Pac FMA area between 2010 and 2023. Examples of how different species respond to overall land base changes include:

Yellow-bellied Flycatcher (-14% overall net change) is typically found in young deciduous and pine forest stands, where it conceals its nest in thick moss or dense understory vegetation.

Alder Flycatcher (+8 overall net change) is associated with young harvested stands.

Black-backed Woodpecker (+19% overall net change) is associated with outbreaks of bark- and wood-boring beetles in recently burned coniferous forests.

The graphs shown below compare the effects of:

- Forestry: New forestry footprint (harvested between 2010 and 2023), regenerating old forestry footprint (harvested before 2010 and continuing to regenerate), and net change.

- Other human footprint: New footprint (created between 2010 and 2023), old footprint (present before 2010), and net change.

- All human footprint combined.

- Natural processes: Fire (areas burned between 2010 and 2023), aging of stands (undisturbed and continued to age between 2010 and 2023), and net change.

- All land base changes combined.

Bird Species' Responses to Land Base Changes. Distribution of bird species’ responses to each type of land base change, summarized as the per cent change in habitat suitability in the Al-Pac FMA area. Points are species, shaded rectangles are the 5% to 95% quantiles, and black lines are the medians.

- Between 2010 and 2023 in the Al-Pac FMA area, changes in bird habitat suitability due to natural disturbances—such as wildfire (-11% to +26%) and the aging of naturally disturbed stands (-13% to +19%)—were greater than those caused by all human disturbances combined (-9% to 4%). The Brown Creeper saw the largest increase in habitat suitability with the aging of naturally disturbed stands (+19%), as it relies on the standing dead trees common in older forests to forage for insects, spiders, and larvae found beneath their peeling bark. The Golden-crowned Kinglet showed the greatest decline in habitat suitability from wildfire (-11%), as it depends on the dense foliage of mature conifers for both foraging and nesting cover.

- Between 2010 and 2023, more bird species showed decreases (59%) than increases (41%) in habitat suitability associated with new forestry, with changes ranging from –10% to +8%. The largest declines were observed for old-forest specialists such as the Black-throated Green Warbler (–10%) and Bay-breasted Warbler (–6%). In contrast, early-seral species like the Alder Flycatcher (+8%) and Clay-colored Sparrow (+5%) increased in suitability, benefiting from shrubby habitats created after disturbance. The aging of older harvest areas partially offset these effects, narrowing the net forestry-related change to between –9% and +4%.

- When examining the effects of new human footprint (excluding forestry), changes in bird habitat suitability were generally small (ranging from –1% to +1%). However, more bird species showed decreases (83%) than increases (17%) in suitability—compared with wildfire (64% decrease) and the natural aging of disturbed stands (54% decrease).

- There were nine species with more than 5% net loss of habitat due to combined land base changes between 2010 and 2023. The majority of these species, including the Yellow-bellied Flycatcher (-14%) and Ovenbird (-10%), are primarily associated with young to mid-aged forest habitats and lose habitat as forest stands mature.

- There were seven species with at least a 5% increase in habitat suitability overall. This included species that rely on recent fires for habitat, such as the Black-backed Woodpecker (+19%), as well as species that prefer habitats created after fire and forestry that can provide dense cover for nesting, such as the Mourning Warbler (+7%).

Land Base Change. Effects of different types of land base change on {speciesName} in the Al-Pac FMA area from 2010–2023. Hover over each land base category to see the predicted per cent change in habitat suitability for that land base type.

Mammals

The graph below shows the distribution of mammal species' responses to each type of land base change in the Al-Pac FMA area between 2010 and 2023. Examples of how different species respond to overall land base changes include:

.jpg)

Canada Lynx (-2% overall net change) rely on dense regenerating forest that supports their main prey, Snowshoe Hare, and on mature forest for cover and denning.

_Canis%20lupus.jpg)

Gray Wolf (+2% overall net change) is adaptable to a variety of habitats, so long as prey species are available and the habitat is isolated from people.

White-tailed Deer (+3% overall net change) are attracted to early-successional habitats created by recent fire or forestry, where new growth of shrubs, forbs, and grasses provides high-quality browse.

The graphs shown below compare the effects of:

- Forestry: New forestry footprint (harvested between 2010 and 2023), regenerating old forestry footprint (harvested before 2010 and continuing to regenerate), and net change.

- Other human footprint: New footprint (created between 2010 and 2023), old footprint (present before 2010), and net change.

- All human footprint combined.

- Natural processes: Fire (areas burned between 2010 and 2023), aging of stands (undisturbed and continued to age between 2010 and 2023), and net change.

- All land base changes combined.

Mammal Species' Responses to Land Base Changes. Distribution of mammal species’ responses to each type of land base change, summarized as the per cent change in habitat suitability in the Al-Pac FMA area. Points are species, shaded rectangles are the 5% to 95% quantiles, and black lines are the medians.

- In the Al-Pac FMA area, change in mammal species’ habitat suitability was small for all types of land base changes combined, ranging from -2% to +3%.

- Most large mammals detected with wildlife cameras are habitat generalists that can use a wide range of habitats and/or are more responsive to changes in the availability of forage or of prey.

Land Base Change. Effects of different types of land base change on {speciesName} in the Al-Pac FMA area from 2010–2023. Hover over each land base category to see the predicted per cent change in habitat suitability for that land base type.

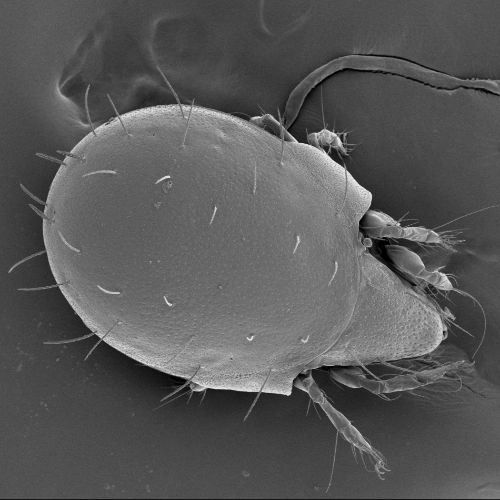

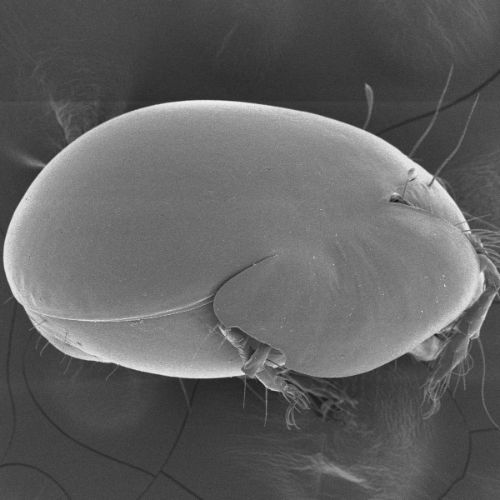

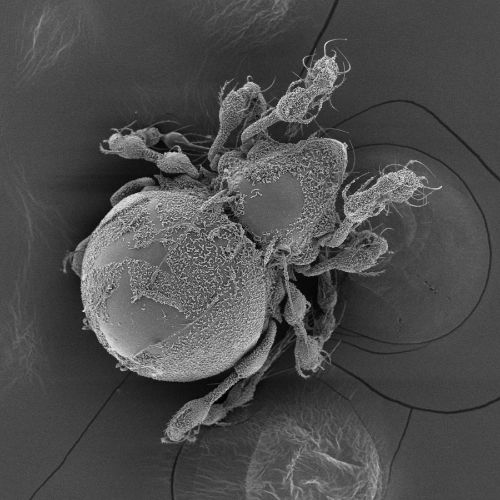

Soil Mites

The graph below shows the distribution of soil mite species' responses to each type of land base change in the Al-Pac FMA area between 2010 and 2023. Examples of how different species respond to overall land base changes include:

Peloribates sp. 3 DEW (-15% overall net change) is associated with upland forest habitats.

Neoribates sp. 2 DEW (-15% overall net change) is associated with young to mid-aged forests.

Epidamaeus sp. 1 DEW (+16% overall net change) responded most strongly to native aging.

The graphs shown below compare the effects of:

- Forestry: New forestry footprint (harvested between 2010 and 2023), regenerating old forestry footprint (harvested before 2010 and continuing to regenerate), and net change.

- Other human footprint: New footprint (created between 2010 and 2023), old footprint (present before 2010), and net change.

- All human footprint combined.

- Natural processes: Fire (areas burned between 2010 and 2023), aging of stands (undisturbed and continued to age between 2010 and 2023), and net change.

- All land base changes combined.

Soil Mite Species' Responses to Land Base Changes. Distribution of soil mite species’ responses to each type of land base change, summarized as the per cent change in habitat suitability in the Al-Pac FMA area. Points are species, shaded rectangles are the 5% to 95% quantiles, and black lines are the medians.

- When all land base changes are combined, habitat suitability declined across the Al-Pac FMA area for 69% of soil mite species between 2010 and 2023 ranging from a 37% loss of habitat to a 16% gain.

- Habitat suitability declined for 64% of soil mite species (ranging from -6% to +8%) as a result of new forestry activities between 2010 and 2023. Aging of previously harvested forest areas led to improved habitat conditions for 57% (-5% to +3%) of species—partially offsetting these losses. However, the overall net effect of forestry was still negative, with habitat suitability declining for 62% (-7% to +5%) of species. Forest harvest can decrease the availability and diversity of leaf litter, which reduces the availability and composition of food for soil mites[3].

- The range of habitat suitability changes due to fire (-14% to +28%) as well as the aging of naturally disturbed stands (-23% to +30%)—indicates that some mite species respond more strongly to natural changes than to human footprint.

- Habitat suitability dropped by at least 10% for ten species due to combined changes on the land base. For example, Peloribates sp. 3 DEW (-15%) and Neoribates sp. 2 DEW (-15%), which are associated with young to mid-aged forests (20–60 years), declined as natural stands aged.

- The species with the largest gains in habitat had stronger responses to natural land base changes than to changes due to forestry or other human footprint. Scutozetes lanceolatus (+10%) and Eupelops septentrionalis (+10%) responded most strongly to fire, while Epidamaeus sp. 1 DEW (+16%) responded most strongly to native aging.

Land Base Change. Effects of different types of land base change on {speciesName} in the Al-Pac FMA area from 2010–2023. Hover over each land base category to see the predicted per cent change in habitat suitability for that land base type.

Vascular Plants

The graph below shows the distribution of vascular plant species' responses to each type of land base change in the Al-Pac FMA area between 2010 and 2023. Examples of how different species respond to overall land base changes include:

Cow Wheat (-38% overall net change) prefers dry to mesic habitats in open coniferous or mixedwood forests, often on sandy or rocky, well-drained soils.

Blue Columbine (-29% overall net change) prefers moist habitats found in mature/old coniferous forests and riparian areas.

Bicknell’s Geranium (+24% overall net change) is strongly associated with recently burned forest stands.

The graphs shown below compare the effects of:

- Forestry: New forestry footprint (harvested between 2010 and 2023), regenerating old forestry footprint (harvested before 2010 and continuing to regenerate), and net change.

- Other human footprint: New footprint (created between 2010 and 2023), old footprint (present before 2010), and net change.

- All human footprint combined.

- Natural processes: Fire (areas burned between 2010 and 2023), aging of stands (undisturbed and continued to age between 2010 and 2023), and net change.

- All land base changes combined.

Vascular Plant Species' Responses to Land Base Changes. Distribution of vascular plant species’ responses to each type of land base change, summarized as the per cent change in habitat suitability in the Al-Pac FMA area. Points are species, shaded rectangles are the 5% to 95% quantiles, and black lines are the medians.

- Between 2010 and 2023, vascular plant species exhibited a roughly even balance of positive and negative responses to changes in habitat suitability across the entire land base, with individual species showing shifts ranging from a 38% decrease to a 37% increase.

- The impacts of natural disturbances on vascular plant habitat suitability during this period were mixed. Wildfire reduced suitability for 59% of species, with changes ranging from –31% to +44%, while aging of naturally disturbed stands increased suitability for about half of species (–20% to +21%). Many vascular plants are long-lived, shade-tolerant species associated with older, closed-canopy forests; they typically decline after fire and harvesting but increase as forests mature. For example, Canada Anemone thrives in the moist, well-drained soils of mature and old forests.

- Changes in habitat suitability due to forestry (-6% to +16%) were smaller than those from natural disturbance. Between 2010 and 2023, habitat suitability declined for 60% of vascular plant species affected by forestry. However, many species benefit from the increased sunlight and reduced competition following canopy removal; for example, Alpine Milk Vetch (+16%) thrives in the full sun and open conditions of recently harvested areas.

- Habitat suitability declined by more than 10% for nine species as a result of all land base changes combined between 2010 and 2023. All nine of these species—such as Cow Wheat (-38%), and Blue Columbine (-29%)—had strong negative responses to the net effect of fire and aging.

- There were 21 species with habitat gains of more than 10% as a result of all land base changes combined. Most of these species prefer early seral habitat and respond negatively to aging of naturally disturbed stands and harvest areas. For example, Hay Sedge (+25%) and Bicknell’s Geranium (+24%) both respond positively to disturbance by fire.

Land Base Change. Effects of different types of land base change on {speciesName} in the Al-Pac FMA area from 2010–2023. Hover over each land base category to see the predicted per cent change in habitat suitability for that land base type.

Mosses

The graph below shows the distribution of moss species' responses to each type of land base change in the Al-Pac FMA area between 2010 and 2023. Examples of how different species respond to overall land base changes include:

Red Leaf Moss (-25% overall net change) is commonly found on decaying wood, humus, or moist soil in shaded, mature coniferous forests.

Slender-stemmed Hair Moss (-19% overall net change) is commonly found on dry, exposed soil, rock, or thin humus in open forests and rocky outcrops.

Umbrella Liverwort (+22% overall net change) is commonly associated with young or recently disturbed forest stands, including areas affected by fire.

The graphs shown below compare the effects of:

- Forestry: New forestry footprint (harvested between 2010 and 2023), regenerating old forestry footprint (harvested before 2010 and continuing to regenerate), and net change.

- Other human footprint: New footprint (created between 2010 and 2023), old footprint (present before 2010), and net change.

- All human footprint combined.

- Natural processes: Fire (areas burned between 2010 and 2023), aging of stands (undisturbed and continued to age between 2010 and 2023), and net change.

- All land base changes combined.

Moss Species' Responses to Land Base Changes. Distribution of moss species’ responses to each type of land base change, summarized as the per cent change in habitat suitability in the Al-Pac FMA area. Points are species, shaded rectangles are the 5% to 95% quantiles, and black lines are the medians.

- Between 2010 and 2023 in the Al-Pac FMA area, changes in habitat suitability for mosses due to natural factors—including fire (-12% to +25%) and the aging of naturally disturbed stands (-16% to +16%)—were greater than those caused by human disturbances including forestry (-7% to +9%) and from other human footprint (-1% to +4%).

- Across all disturbances, habitat suitability declined for the majority of moss species, with other human footprint having the strongest negative effect (88% of species), followed by forestry (71%) and fire (70%). Most moss species depend on the cool, moist conditions provided by mature and old forests and respond negatively to canopy removal.

- In forestry areas, the drop in habitat suitability from new harvesting between 2010 and 2023 was mostly balanced by forest aging, which improved habitat suitability for 69% of moss species.

- There were six species with more than 10% net loss of habitat due to combined land base changes between 2010 and 2023. All of these species—such as Red Leaf Moss (-25%) and Slender-stemmed Hair Moss (-19%)—had strong negative responses to the net effect of fire and aging.

- There were five species with habitat gains of more than 10% as a result of all land base changes combined. All of these species had a strong positive response to fire.

Land Base Change. Effects of different types of land base change on {speciesName} in the Al-Pac FMA area between 2010 and 2023. Hover over each land base category to see the predicted per cent change in habitat suitability for that land base type.

Lichens

The graph below shows the distribution of lichen species' responses to each type of land base change in the Al-Pac FMA area between 2010 and 2023. Examples of how different species respond to overall land base changes include:

Peppered Pelt (-7.9% overall net change) is commonly found on bark of conifer trees in open, well-lit forests and along forest edges.

Common Clam Lichen (-22% overall net change) typically grows on bark of conifer trees in open, well-lit forests and along forest edges.

Peg-leg Soldiers (+11% overall net change), typically grows on thin soil or exposed rock in open, well-drained sites such as rocky outcrops and open coniferous forests.

The graphs shown below compare the effects of:

- Forestry: New forestry footprint (harvested between 2010 and 2023), regenerating old forestry footprint (harvested before 2010 and continuing to regenerate), and net change.

- Other human footprint: New footprint (created between 2010 and 2023), old footprint (present before 2010), and net change.

- All human footprint combined.

- Natural processes: Fire (areas burned between 2010 and 2023), aging of stands (undisturbed and continued to age between 2010 and 2023), and net change.

- All land base changes combined.

Lichen Species' Responses to Land Base Changes. Distribution of lichen species’ responses to each type of land base change, summarized as the per cent change in habitat suitability in the Al-Pac FMA area. Points are species, shaded rectangles are the 5% to 95% quantiles, and black lines are the medians.

- Between 2010 and 2023 in the Al-Pac FMA area, changes in lichen habitat suitability driven by natural factors—such as wildfire (–14% to +16%) and the aging of naturally disturbed stands (–13% to +23%)—were greater than those caused by human disturbances, including forestry (–11% to +4%) and other human footprint (–1% to +1%).

- During this period, habitat suitability declined for most lichen species in response to new disturbances: 95% were affected by other human footprint, 92% by wildfire, and 84% by new forestry. Many lichen species depend on mature trees, dead wood, or stable rock surfaces for growth, making them sensitive to both natural and human disturbance.

- Habitat suitability improved for 80% of species as harvested areas aged, helping to offset some of the negative impacts of forestry.

- Eight species experienced more than a 10% net loss of habitat due to combined land base changes, with wildfire being the primary driver. For example, habitat suitability declined for American Starburst (–28%) and Common Clam Lichen (–22%) both favor stable, shaded habitats with mature trees and decaying wood.

- There were three lichen species with at least a 10% increase in habitat due to combined land base changes: Two-toned Tube Lichen (+11%), Salted Shield (+11%), and Peg-leg Soldiers (+11%). All three species had strong positive responses to different types of natural disturbance—forest aging, the net effect of fire and aging, and wildfire, respectively.

Land Base Change. Effects of different types of land base change on {speciesName} in the Al-Pac FMA area from 2010–2023. Hover over each land base category to see the predicted per cent change in habitat suitability for that land base type.

Caveats

- These changes reflect the predicted changes in species’ habitat suitability due to changes in the land base that we can map. Many other factors can also change species’ populations. We will be able to look into those when we have direct trend information, which we can then compare to the changes predicted from land base change.

- These predicted effects of land base change are based on the period 2010–2023. Harvest rates, and particularly fires, vary over time. The ABMI will soon have province-wide mapping for the year 2000, so that we can extend the attribution analysis over a longer time period.

- The results are based on ABMI habitat models, which are imperfect and improve over time as we collect more data.

References

Best, I.N., L. Brown, C. Elkin, L. Finnegan, C.J.R. McClelland, C.J. Johnson. 2024. Cut vs. Fire: A Comparative Study of the Temporal Effects of Timber Harvest and Wildfire on Ecological Indicators of the Boreal Forest. Landscape Ecology 39(4): 81. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10980-024-01882-4.

Alberta-Pacific Forest Industries Inc. 2022. Alberta-Pacific Forest Products Inc. Forest Management Agreement Area Forest Stewardship Report. Alberta-Pacific Forest Industries Inc. Available at: https://alpac.ca/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/Al-Pac-Stewardship-Report-2015-2020_complete_NCedit_21May21_final.pdf.

Alberta Biodiversity Monitoring Institute. 2024. Effects of 2023 Wildfires in Alberta. Available at: https://abmi.ca/publication/642.html.

Methods for summarizing attributions of habitat change are described in Section 1.3.3.

.svg)